Lecturer in Criminology & Investigative Psychology

Kingston University London, Criminology and Sociology | Psychology

A Lecturer in Criminology & Investigative Psychology at Kingston University London and a Visiting Researcher at UCL. My research focuses on Deception Detection, Emotions, and Judgement under uncertainty. My focus is on uncovering the diagnostic value of the non-conscious nonverbal behaviours that people exhibit when communicating, especially when they are attempting to lie and/or mislead others. My current research is on improving the abilities to accurately detect deception by investigating how facial expressions of emotion are faked and under what circumstances can people detect them. Currently, my work has focused on the role of Trust and Reputation in Sharing Economies, collaborating with Computer Science department at UCL.

Kingston University London, Criminology and Sociology | Psychology

Teesside University, Psychology

University College London, Computer Science

University College London, Experimental Psychology

University College London, Psychology and Language Sciences

University College London, Psychology Department

University College London, Psychology Department

University College London, Psychology Department

Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, Advance.HE

Higher Education Academy

Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology

University College London

Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, Advance.HE

Higher Education Academy

Master in Social Cognition

University College London

Bachelor of Science in Psychology

Goldsmiths College London

My research interests relate to Nonverbal Communication and Deception Detection. My focus is on uncovering the diagnostic value of the non-conscious nonverbal behaviours that people do when communicating, especially when they are attempting to lie and/or mislead others.

The current focus of my work is to improve the abilities of others to accurately detect deception by investigating which nonverbal cues are relevant to deception detection and under what circumstances they can be used. My work considers the importance of the type of lie that is told, the circumstances surrounding the situation, as well as factors that may affect the detection process.

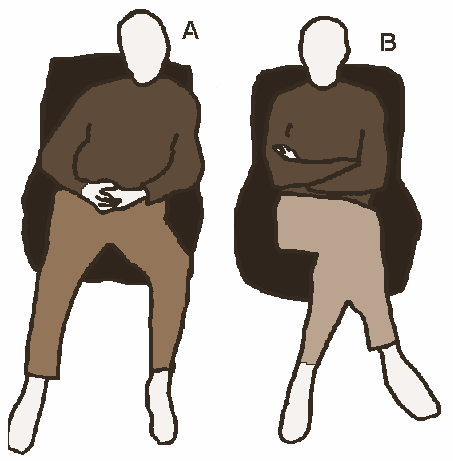

During my MSc in Social Cognition I focused on embodiment and social acuity by studying the effect that adopting either a "closed" or "open" body posture would have on correctly recognizing facial expressions of emotion and detecting deception in others. This work allowed me to uncover novel methods of improving accuracy of lie detection as well as improve our understanding of how people use social information to make judgements about others.

My PhD focused on uncovering the importance of emotions for lying and deception detection, attempting to understand the usefulness of these cues and their limitations. The experiments I conduct offer a more detailed understanding of both how individuals behave when they lie, and how detectors can use the information available to them to have the highest accuracy possible. My research also expands to areas of body postures, particularly the effect they have on the person adopting specific postures when interacting with others, as well as differences in judgements and decision making made alone or in groups.

Currently, the projects I am undertaking focus on the role of Trust and Reputation in Sharing Economies, as part of a larger EPSRC grant, with focus on the behavioural aspects of these processes.

In a series of online experiments, we investigate the effect of community-generated trust and reputation information (TRI) on user decision-making and choice preference on Sharing Economy platforms. The results over several studies strongly support our claim that TRI produces a positivity bias in users' perception of other users (here, Hosts). This work illustrates the strength of TRI on user judgement, its limitation as a metric for quality, and the cognitive bias people experience in this novel online peer-to-peer environment.

This experiment looked at how the context in which individuals are interrogated affects how believable they appear. Participants were videotaped while providing truthful or fabricated responses in an interrogation setting while their ability to gesticulate freely was manipulated. The manipulation was achieved by handcuffing half of the participants. Deception detection accuracy, confidence and bias for the two conditions was obtained from both layperson and police officers. The study looks at how the physical constraints imposed on the “suspects” affects their ability to appear honest and on how these constraints affect the decoder’s accuracy and suspiciousness.

How do people fake emotions, and how convincing are they? Participants were recorded reacting to a surprising stimulus, a vampire jack-in-the-box, and faking surprise to a neutral stimulus, a countdown timer. Half the participants faked surprise before experiencing genuine surprise (improvise condition), and the other half afterwards (rehearse condition). These recordings were shown to other participants who tried to identify which were genuine. The improvised surprise was easier to classify as fake, compared to rehearsed surprise, which was indistinguishable from genuine surprise. The improvised and rehearsed expressions were rated as equally intense, and both less so than the genuine surprise. These results show that the experience of surprise helps participants convincingly portray that emotion later. Further experiments will reveal what aspects of rehearsal aid performance, whether participants are drawing on their recent internal experience of genuine surprise, or a motor memory of their recent behaviour when genuinely surprised.

Emotion theories of deception state that information relating to one’s true emotions is useful in determining if they are lying or telling the truth. The current study investigated accuracy of deception detection based on differences in one’s ability to accurately recognise emotional cues in low-stake lies, where the consequences or rewards to the deceiver are low. The study compared participants on subtle cue recognition, microexpression detection, empathy, and alexithymia. The results reveal that one’s ability to detect facial cues was not related to accuracy. Empathy and deception detection showed a negative correlation, suggesting higher trait empathy is detrimental to accuracy, while alexithymia did not relate to either emotion recognition or deception detection. The findings illustrates that the relationship between emotion recognition in low-stakes lies differs from that observed in other types of lies, and that different component of emotion recognition have different relationships with the deception detection process.

Emotion theories of deception state that cues relating to the true emotions of a deceiver leak out during deception (Ekman & Friesen, 1969). Although such cues are said to be ubiquitous, research investigating their usefulness in deception detection shows inconsistent results. A potential issue is the role of moderating factors that determine cue production, such as the stakes to the liar for deceiving. The current study investigated the effect of emotion recognition training and bogus training on accuracy in detecting lie where the stakes to the deceiver were low or high. The results showed that in both deception conditions neither emotion recognition training nor bogus training was useful in improving accuracy, but that low-stakes lies and emotional lies were easier to detect. The potentially paradoxical results are discussed in terms of a dual system model of emotion recognition in deception detection.

When people judge whether others are lying or telling the truth, they act differently if they are working alone or in a group. The current experiment explored this finding by varying the amount of information that participants (working alone or in a pair) could communicate while making veracity decisions. The information that participants provided varied on three levels: a binary truth/lie decision, a binary decision and a set of reasons chosen from a list, or an open ended discussion/explanation. Being alone or in a pair had no significant effect on accuracy, but confidence was higher in the pair condition. A truth bias was found in the single condition but was mostly eliminated for pairs. As was predicted, the amount of information provided after each decision had an effect on accuracy, bias, and confidence. Lie detection accuracy was highest when stating a reason chosen from a list, while confidence increased with the amount of information provided. In pairs, specifying a reason or conversing while making the veracity decision eliminated the truth bias. The current findings improve our understanding of the effect of pair decision making, illustrating how varying levels of information can have different effect on decision making and deception detection.

Previous research has indicated that body postures have significant effects on the way individuals process social information, but little is known of the effect postures may have on social acuity and the recognition of behavioural cues. The current study investigated the effect of open and closed body postures on the recognition of facial expressions of emotion and deception detection. It was hypothesised that adopting an Open posture would result in improved recognition of all seven universal expressions, compared to a Closed posture. Secondly, the Open posture would improve accuracy of deception detection, due to the improvement in recognition of cues of deception. Differences in empathy were also considered, as empathy is an important individual difference relating to the accurate recognition of emotional states in other, predicting that individuals with higher self-reported empathy would outperform individuals with lower empathy scores on both facial expression recognition and deception detection. The results showed partial support for the experimental hypotheses, finding that Open postures improved accuracy of truth detection, but not of lie detection. No effect of posture was found for the recognition of facial expression of emotion. The predicted advantage of higher trait empathy was found for truth detection, but no effect for either the lie detection or for facial expression recognition. The results are discussed in terms of theories of social acuity and information processing, as well as their implications in the field of deception detection. Potential limitations and future research directions are also discussed.

This experiment will focus on the ability of individuals to match facial expressions with congruent or incongruent descriptions of emotional states. It will focus both on established facial expressions of emotions and potentially novel conversational expression. The experiment will involve online data collection from a diverse sample of participants, in the hopes of providing a highly ecologically valid understanding of how well people can classify the emotional expressions of others. The study aims to find initial data on this new conversational expression that relates to genuine interest and acceptance of novel information.

Below is a list of ongoing research and publications.

People are good at recognizing emotions from facial expressions, but less accurate at determining the authenticity of such expressions. We investigated whether this depends upon the technique that senders use to produce deliberate expressions, and on decoders seeing these in a dynamic or static format. Senders were filmed as they experienced genuine surprise in response to a jack-in-the-box (Genuine). Other senders faked surprise with no preparation (Improvised) or after having first experienced genuine surprise themselves (Rehearsed). Decoders rated the genuineness and intensity of these expressions, and the confidence of their judgment. It was found that both expression type and presentation format impacted decoder perception and accurate discrimination. Genuine surprise achieved the highest ratings of genuineness, intensity, and judgmental confidence (dynamic only), and was fairly accurately discriminated from deliberate surprise expressions. In line with our predictions, Rehearsed expressions were perceived as more genuine (in dynamic presentation), whereas Improvised were seen as more intense (in static presentation). However, both were poorly discriminated as not being genuine. In general, dynamic stimuli improved authenticity discrimination accuracy and perceptual differences between expressions. While decoders could perceive subtle differences between different expressions (especially from dynamic displays), they were not adept at detecting if these were genuine or deliberate. We argue that senders are capable of producing genuine-looking expressions of surprise, enough to fool others as to their veracity.

This experiment looked at how the context in which individuals are interrogated affects how believable they appear. Participants were videotaped while providing truthful or fabricated responses in an interrogation setting while their ability to gesticulate freely was manipulated. The manipulation was achieved by handcuffing half of the participants. Deception detection accuracy, confidence and bias for the two conditions was obtained from both layperson and police officers. The study looks at how the physical constraints imposed on the “suspects” affects their ability to appear honest and on how these constraints affect the decoder’s accuracy and suspiciousness.

The ability to recognise the emotional states of others is believed to facilitate the detection of deception, but the exact way in which individuals use emotional information during deception detection has not been fully explored. In this paper, the current way of thinking about deception detection is reviewed and extended by a discussion about the importance of the stakes to the liar in emotion cue production. For the perception of emotion cues, individual differences in empathic ability are proposed to be a crucial moderator of the relationship between emotion recognition and deception detection. This ability may facilitate deception detection under certain circumstances but may hinder accuracy in others. The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of the way emotions relate to both the process of deception and its detection, and propose possible future avenues of research in this area.

Humans have developed a complex social structure which relies heavily on communication between members. However, not all communication is honest. Distinguishing honest from deceptive information is clearly a useful skills, but individuals do not possess a strong ability to discriminate veracity. As others will not willingly admit they are lying, one must rely on different information to discern veracity.

Many books teach the mechanics of using Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube to compete in business. But no book addresses how to harness the incredible power of social media to make a difference. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

In deception detection, individuals are told to rely on behavioural indices to discriminate lies and truths. A source of such indices are the emotions displayed by another. This thesis focuses on the role that emotions have on the ability to detect deception, exploring the reasons for low judgemental accuracy when individuals focus on emotion information. I aim to demonstrate that emotion recognition does not aid the detection of deception, and can result in decreased accuracy. This is attributed to the biasing relationship of emotion recognition on veracity judgements, stemming from the inability of decoders to separate the authenticity of emotional cues.

To support my claims, I will demonstrate the lack of ability of decoders to make rational judgements regarding veracity, even if allowed to pool the knowledge of multiple decoders, and disprove the notion that decoders can utilise emotional cues, both innately and through training, to detect deception. I assert, and find, that decoders are poor at discriminating between genuine and deceptive emotional displays, advocating for a new conceptualisation of emotional cues in veracity judgements. Finally, I illustrate the importance of behavioural information in detecting deception using two approaches aimed at improving the process of separating lies and truths. First, I address the role of situational factors in detecting deception, demonstrating their impact on decoding ability. Lastly, I introduce a new technique for improving accuracy, passive lie detection, utilising body postures that aid decoders in processing behavioural information.

The research will conclude suggesting deception detection should focus on improving information processing and accurate classification of emotional information.

Although a substantial amount of research has examined the constructs of warmth and competence, far less has examined how these constructs develop and what benefits may accrue when warmth and competence are cultivated. Yet there are positive consequences, both emotional and behavioral, that are likely to occur when brands hold perceptions of both. In this paper, we shed light on when and how warmth and competence are jointly promoted in brands, and why these reputations matter.

A brief summary of the main teaching related activities. These reflect both teaching engagements, lecturing, and mentoring.

I also hold the title of Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (HEA) that I received to acknowledge my teaching activities within a higher education environment.

Module: Applied Quantitative Research Methods.

Module: Applied Forensic Psychology.

Module: Law, Justice and Psychology.

Module: The Psychology of Investigations.

Module: The Psychology of Criminal and Sexual Offending.

I provide one-on-one tutoring for students struggling with their exams. The topics I cover are BSc, MSc, and PhD level Statistics, BSc Psychology, and MSc Research Methods.

Affective Neuroscience and Psychophysiology Colloquium, University of Göttingen

Financial Computing & Analytics Seminars, CS | University College London

I was a demonstrator for an undergraduate BSc Psychology module for 2nd years. Involves designing quantitative and qualitative experiments, hypothesis generation, data analysis and interpretation.

My role was to supervise a group of ten 1st year undergraduate students while they learn the basics of experimental design and statisical analysis. My main tasks involve explaining the proper way to write a lab report, and to provide feedback on their performance through out the academic year.

MSc Social Cognition thesis.

BSc Psychology (2nd and 3rd Years) final projects.

MSc Computer Science Students final projects.

ICN Seminars - Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, ICN | University College London

Understanding Individuals and Groups module for the MSc in Social Cognition, EP | University College London

Cognitive Psychology Course for the MSc in Research Methods, EP | University College London

Cognitive Psychology Course for the MSc in Research Methods, EP | University College London

Applied Social Psychology MSc module, EP | University College London

Introduction to Social Psychology Course, New York University

Cognitive Psychology Course for the MSc in Research Methods, EP | University College London

Co-chair to the Psychology and Language Sciences Division PhD support program.

MSc and BSc Statistics and Research Methods.

A few photographs illustarting various aspects of research life

If you would like to discuss my work in more detail, or would like to contact me regarding work in the field of deception detetion, nonverbal communication or social psychology. I am able to provide support and consultancy services in these areas for both academic and business related purposes. If you would like to collaborate on a research project please contact me by email directly.

You can find me at my office located at Kingston University London, MB3028, Penrhyn Road, Kingston, UK.

I have office hours on Tuesday and Thursday between 9:00 and 18:00, but you may consider an email to fix an appointment.

Coming soon using R Blogdown.

To see work from my former lab click the link below